DevSecOps weekly, eighth issue, part 2

This is a continuation from my previous post, where I turned simple problem description in to a conceptual model of a database. On this post I will go through the steps on how to turn it to a full-blown schema of a database!

Overview

Database schema is a way of finalizing the design of the database. It is a model that represents all the necessary details on how each defined concept can be turned in to database tables using SQL-syntax.

You might wonder, what is even missing at this point. We have each concept, their attributes and even the relations down on the conceptual model created on last blog. Well, in relational databases nothing is actually related to each other, unless certain keys are in place.

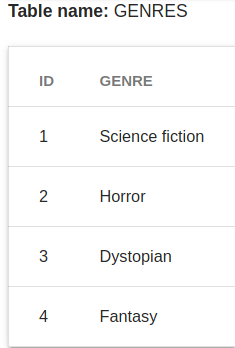

Before going any further I’d like to present a very simple example of a table:

Why I want to present this here is simple; when talking about columns (marked as ID an GENRE in the picture) and rows (1 and Science fiction etc.) it is much easier to understand via a screen capture. Source of example is one of Introductory to Databases MOOC’s training tables.

In relational model, every concept is its own table and every attribute of that concept is a column in their respective table. Each row in that table is an instance of concept, all of which are identified with a unique numeric value assigned to them. Since we are now turning concepts in to tables, I will refer them as such from now on, unless there is a need to refer to pre-schema form.

The unique numeric value column is usually used as a primary key of a table. It is also possible to have group of columns to act as of primary key, but it is outside the scope of this post. As such, you can think of the primary key to be equal to identification number. The primary key column actually is usually known as id, since it is used to identify an instance.

Knowing this and going back to example picture we can see that genre called Horror with an id of 2 AND genre called Dystopian with and id of 3, are instances of Genres. All the rows presented on the picture are instances of that one concept.

Thus far we have each row identified with a unique number to that row. Now that it is possible to discern rows from each other, it is also possible to start connecting rows from different tables to each other. To do that, foreign key is needed. It is a column in a table that includes value of other tables primary key.

Each value in a foreign key column is related to primary key column somewhere else. This is how the relation between two tables is made and is the basis of transforming conceptual model to database schema.

Conceptual model to database schema

To elaborate, database schema provides the structure of a database. It includes all the necessary tables and columns, including the primary and foreign keys. Process of preparing the database schema is also fivefold:

- Define primary keys to concepts

- Process many to many-relations

- Process one to many-relations

- Process one to one-relations

- Finalize datatypes

I will go through each of them under their own header, just like when conceptualizing the problem description.

Define primary keys to concepts

Let’s start with the simplest one. Like said, every concept needs to have their own primary key so that each row can be distinguished from each other. They are “tagged” with (pk) on the schema picture below. Here are the primary keys added to conceptual model:

Other than being always unique (read: two rows with the same ID cannot exist), primary keys have a couple other unique features. First, value must always be present and secondly to prevent identical id’s running numbers are used.

But what does “running” mean in this context? As can be seen ID is an integer type, meaning that they are of numerical value. First row in the table will have a value of 1, second will have value 2 and so forth.

Following this logic, the customer row with id value of 9542456 would mean that the customer in question would have been 9542456th customer registered to the system.

Process many to many-relations

There is a reason why this and the next two steps have the word “process” in them. They critical, as the database is getting its final shape, and possible flaws in design may present themselves. Many to many-relations are connected to each other with something called join table.Join tables are special tables that, well, join two or more tables together. It is used to identify which instances of a table are related to another table’s instance. Looking back to the conceptual model with primary keys added to it we realize that there is one many to many-relation between “Product” and “Category” tables.

Thus, it is necessary to create a brand-new table called “ProdCategory” to the schema:

You may have also noted that the *-*-relation between “Product”- and “Category”-tables is no longer present, but rather has been replaced with one to many-relation to newly created ProdCategory-table. The brand spanking new table is also missing columns, which will be processed on the next step.

Process one to many-relations

The reason why I decided to omit the columns on ProdCategory-table is because the one to many-relation will be explained under this header in detail.

When processing one to many-relations, a new column is created to table that has a *-mark on it. This column contains a foreign key that is associated with another table’s primary key. To recap, foreign key points to primary key, creating a match between two instances of different tables. They are “tagged” with (fk) on the schema picture:

A brief recap from last blog post:

From reading the problem description, it is possible to conclude that one product can have multiple categories, and each category can hold multiple different products. Customer can have multiple product on sale and one customer can offer a bid on multiple products. There can multiple offers on a product. One product can have multiple questions...

Now those same connections are constructed between the tables. Everything seems all right. As said, this is the part where the problems usually arise, for example a foreign key could be in place where it does not belong, such as the “Customer”-table in this case.

Most observant may have noticed that I cut the final part of the recap from last blog, let’s jump right into it at the next header.

Process one to one-relations

Here is the rest of the missing recap:...but one question can have only one answer.

Time to process the final relation type, which is also rarest amongst databases, since same data could have been stored inside one table. Examples why it is a good idea to split data like this, is to protect sensitive data that only certain users or groups should see.

One to one-relations are formed between two tables, where both are be associated with each other on only one matching row.

As such, it creates a situation where each foreign key must be unique. This is defined via “UNIQUE FOREIGN KEY” SQL-syntax, but we will not dwell deeper on that on this post. Most important thing is to realize the difference between one to one and one to many, because on schema they seem similar to each other.

Here is only the one on one-relation without the rest of the tables:

The whole database schema will be displayed completely on the next header, along with the datatype finalization!

Finalize datatypes

I already include a list of data types on last time’s conceptual model blog post. Different SQL database engines provide different kinds of data types, although the very basic data types rarely differ integers, floating points etc. For consistency and making sure that data types are available when creating final SQL syntax, I assume that I’m creating this schema for MySQL.

This is a very important step when finalizing the schema, because only for text strings there are over ten possible data types to choose from. There is significant boost in efficiency to be had, when using the right data types for each situation.

For example, it is not efficient to use MEDIUMTEXT (maximum of 16,777,215 character) to store product name, whereas it is much better for description of the product.

Likewise, it is better to use UNSIGNED MEDIUMINT rather than UNSIGNED SMALLINT for id-columns since SMALLINT only holds maximum value of 65535 whereas MEDIUMINT goes all to way to 16777215. Thus, you can hold 16711680 more customers, products or categories.

Another great idea is to use DECIMAL for floating point numbers for currency, since it is an exact fixed-point number, whereas DOUBLE is a floating-point number, which means that there may be rounding errors present.

Anyway here is the final database schema with data types:

Please note, that data types used are only estimates since the information provided was limited on how the service itself should work, further planning with stakeholders may reveal that they already aim to have this and that many customers, thus reducing the data type might be possible.

Therefore, it is important to have an iterative planning and design with service design, that tightly includes all the stakeholders to plan a perfect solution!

Parting words

What a journey it has been! I felt that I have learned so much this week! When I first started reading the problem description, I had so much doubt in my mind if I can even solve this, but step by step writing it down to this blog while working on the drawings made it so much easier for me to understand the process.

I believe conceptualizing will help me a great deal in a future, since it helps me to look the problem from much wider perspective, rather than just working on one piece of the problem at the time. This way I do not have to fixing something that breaks when I move from one part to another.

Also, I found the link between service design and database design, which I believe will have great effect when cooperation with all the stakeholders is constant and inclusive to all ideas. Input of different kinds of expertise is always important when defining a project.

I sincerely hope, that you get something out of these two posts I made this weekend.

-sorhanp